Regardless of Newhouse’s feelings on the matter, Johnson added over the phone to Jones that the newspaper owner had also helped him with “one or two of the Republicans.”

When the poverty bill came to a vote, it wasn’t incredibly close in the House of Representatives, passing 226-185. Jones voted “aye.”

Outside of Johnson’s intrusion, Newhouse prided himself on noninterference.

In a statement to what was then SU’s School of Journalism, Newhouse wrote that an ideal newspaper owner should have “an intense interest in all of the operation of his newspaper, but who can top that intense interest with an even greater degree of self-control.”

When covering Newhouse’s $15 million gift — $151.1 million in today’s dollars, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — TIME Magazine was less kind. The magazine wrote that Newhouse was “often criticized as a crass financier whose only concern is his profit” and that he has “done little to improve the quality of his often mediocre papers.”

Felsenthal said that, as a newspaper owner, Newhouse wasn’t very interested in influencing the way news was covered. First on his mind, she said, was seeing that his papers had their advertising squared away.

“Johnson and the Vietnam War were the only times Newhouse interfered in the editorial coverage of any editorial report (in) any of his papers,” Meeker told The Daily Orange.

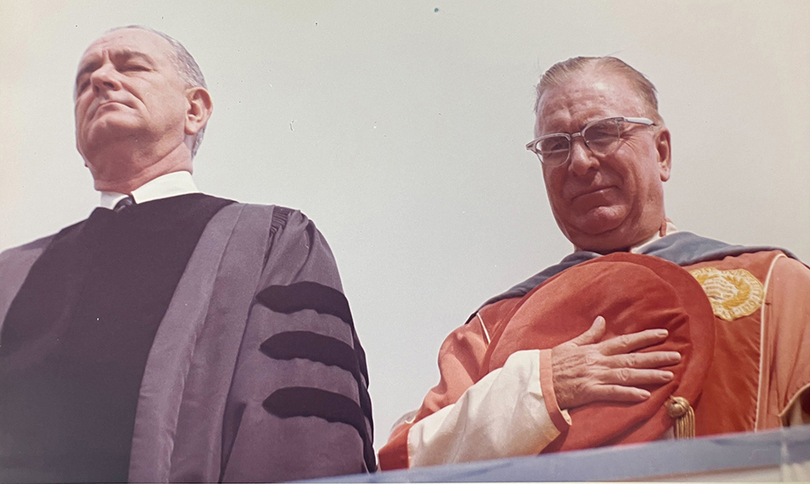

But by speaking at the dedication of his namesake, however, Johnson did Newhouse a huge favor. With that, the newspaper owner’s actions were consistent with a quality he demonstrated throughout his life, Meeker said.

“When someone did him a favor,” Meeker said, “he always tried to repay it.”

LBJ’s call with Jones also wasn’t the first time Newhouse and his papers were discussed in the White House, according to calls stored by LBJ’s presidential library. A week before the president’s trip to Syracuse, LBJ and Edwin Weisl, a friend of Johnson’s, had a phone conversation in which Weisl mentioned that he had called Newhouse with a request.

“He’s calling his editor in New Orleans to put the pressure on Abers on the anti-poverty bill,” Weisl told the president, potentially referring to Mississippi Congressman Thomas Abernethy.

Abernethy did not go with Johnson, voting “nay” along with the entire Mississippi delegation.

He had one arm broken and was not about to have the other one broken as well.Former Chancellor William Tolley

While he did not always positively engage with the media, LBJ had a significant understanding of its importance, said Tom Johnson, who worked as a deputy press secretary under LBJ and shares no familial relation with the former president.

“LBJ was watching the two wire services almost whenever,” said Tom Johnson, who later became the president of CNN. “He was watching the three TVs that he had in his office and bedroom and at the ranch … He was just an enormous consumer.”

Johnson had plenty of friends within the press that he had lunch with, including a columnist at The New York Times and White House correspondents, Tom said. In a 1969 interview, Weisl said he had called the heads of CBS, NBC and ABC “to be sure that they would project the feeling that this was a dedicated man that would be a great President” following John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963.

“I got in touch with Mr. Newhouse who then owned the largest chain of newspapers, and, you know, got him to feel that this President was a great man and would be a great President, and to convey that feeling to the public,” Weisl said.

And if Johnson’s goal was to have the support of Newhouse’s newspapers in the upcoming election against Goldwater, he got it. In his book “Newspaperman,” Meeker notes that, while both of Newhouse’s papers in New Orleans supported Republican Richard Nixon in 1960 and 1968, they endorsed Johnson in 1964.

“Overall, only two Newhouse papers endorsed Goldwater in 1964, while thirteen supported Johnson,” Meeker wrote. “In the nation as a whole, less than five papers out of every ten (42.3%) endorsed Johnson that year.”

Johnson was even more successful in winning the actual election against Goldwater, capturing over 90% of the electoral vote and 61% of the popular vote. He only lost six states, which included Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.

A decade after Johnson’s last days as president, Newhouse died in August 1979. In his obituary, The New York Times characterized Newhouse as a man who did not use his newspapers to push certain ideas on the American public. And outside of his spat with Johnson, that was true.

“I am not interested in molding the nation’s opinion,” Newhouse is quoted as saying in the obituary. “I want these newspapers to take positive stands of their own; I want them to be self-reliant.”